The human factor is traditionally understood to refer to a person’s mistakes: someone presses the wrong button on a work machine, mishears instructions, or forgets to check something.

“But the human factor as a mindset has a much wider meaning. It is defined as factors that affect the individual, work, organisation, group and environment,” says Anna-Maria Teperi, Research Professor at the Finnish Institute of Occupational Health.

The human factor (HF) is also a scientific discipline that explores how human activity and capacity should be taken into account in work planning, training, delegation, and all work organisation.

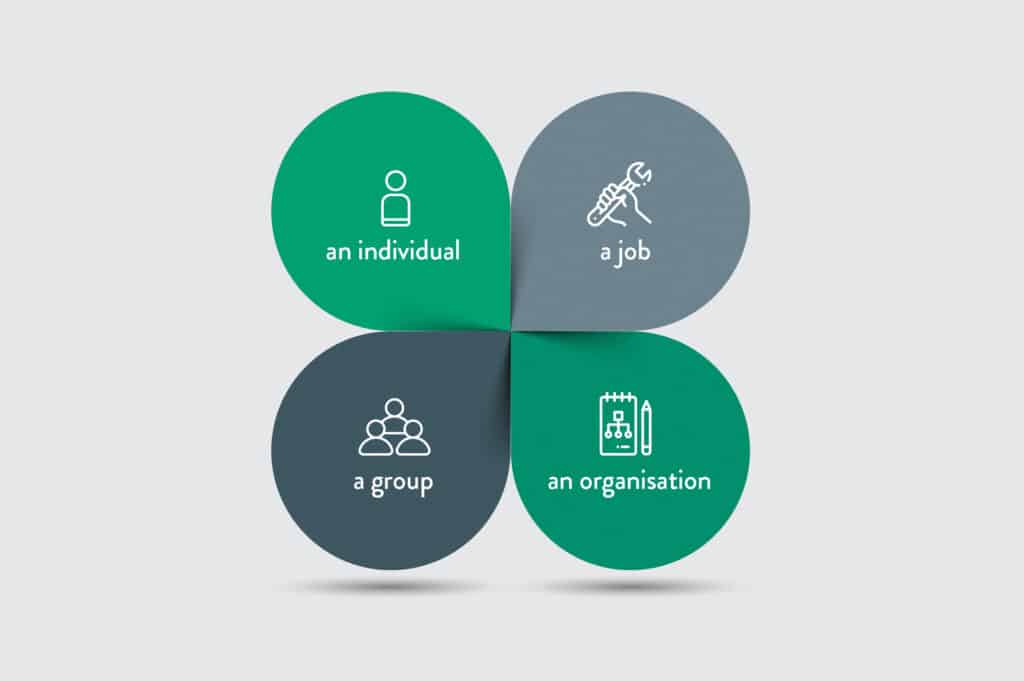

Teperi has developed the HF Tool, which illustrates human factors. It can be thought of as a four-leaf clover where the leaves represent an individual, a job, a group and an organisation.

“The field is very wide,” Teperi points out.

Human factors connected to individuals include professionalism, motivation and attitude. Work-related factors include the amount and type of work, tools and working conditions.

Group activities such as control centres, production or maintenance teams and work groups are concerned with matters such as communication, competence utilisation and atmosphere.

Organisational factors include leadership, the manifestation of leadership, decision-making methods, resources, and procurement methods.

Human factors can be analysed to study deviations and hazards and identify the factors contributing to the situation.

“We can also explore successes in the same way, by looking at what works already,” Teperi says. She gives an example:

“A hazard has occurred in the workplace, but it was only a minor one. Why? Because people were professional, noticed it in time, spoke up, and communicated information, the procedures were clear and the leadership supported the operation.”

Collaboration, analysis and discussion

“Occupational safety is largely thought of as personal protective equipment, helmets, safety shoes and slip prevention. The focus has been on physical risk factors and indivi- dual mistakes: ‘Pekka did it’ or ‘Heikki failed to do it’,” explains Teperi.

She points out that safety is actually about how everyone works together: the interaction between HR management, occupational health and safety, employees and managers and how managers create the conditions for work.

“People´s actions must be taken into account in everything.”

“People’s actions must be taken into account in everything, from management, to work and purchasing tools.”

A Human Factor perspective has helped to create a more analytical understanding of occupational safety, uncovering the reasons behind deviations or successes and identifying areas where improvements are necessary.

Teperi encourages companies that plan to adopt a Human Factor approach to safety work to ensure extensive collaboration between different parties and look at safety as an entity influenced by many factors.

“This facilitates discussion in teams, management groups and various collaborative forums about our strengths and weaknesses – what works well already, which factors were behind any accidents that have happened, and what needs to improve.”

The Human Factor perspective represents a change in mindset, which eventually manifests in positive results in practical work.

“The change requires systematic, long-term and wide-ranging collaboration to meet the goals of a Human Factor mindset: well-being, safety and productivity,” says Teperi.