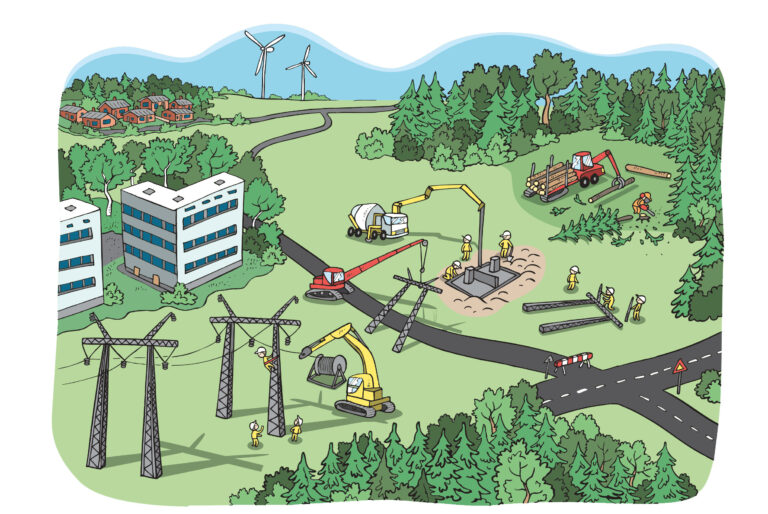

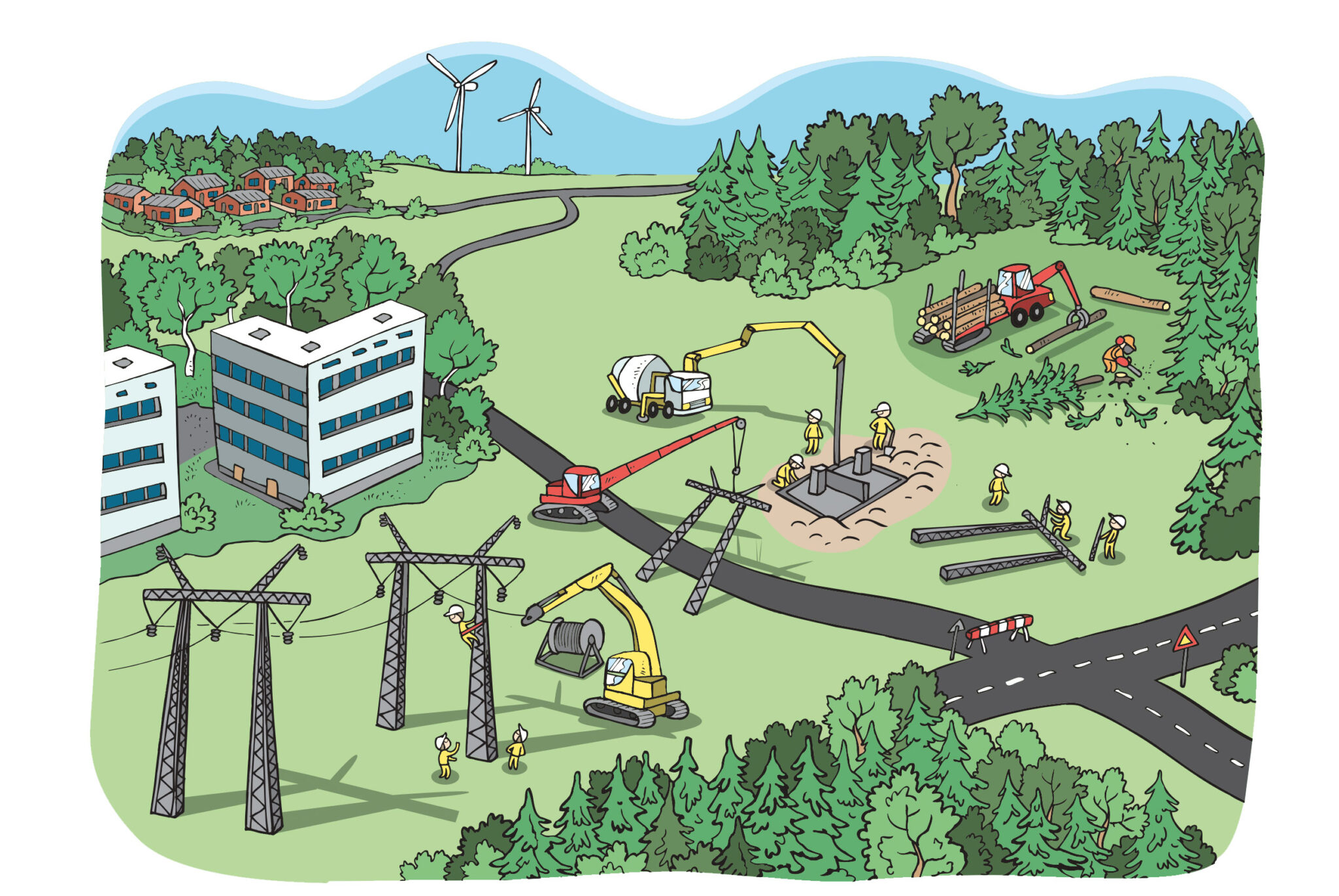

Clean technologies are coming closer to consumers. Fossil fuels should be replaced by wind and solar energy and the resulting demand response, electric cars, heat pumps, energy efficiency, and completely new energy and mobility services. The Paris climate agreement requires that the use of fossil fuels must be phased out by 2050.

The focus has to be shifted to consumers in order to make a successful technical and cultural transition to a carbon-free society. Consumers can be important investors, producers of clean energy and providers of consumption flexibility. In Germany and Denmark, citizens own more than half of the wind and solar power. According to Bank of Finland statistics, Finnish households have deposits of more than 86.7 billion euros in their bank accounts. This should be seen as an opportunity to accelerate the clean energy business.

An energy culture that values centralisation still prevails in Finland. We have the old-fashioned view that big is beautiful and small is expensive. However, if we want to successfully reduce emissions and create new energy business, we should strive for consumer participation and investments in addition to seeking cost effectiveness.

Citizens in Finland have mostly been left outside energy policy. Concrete examples of this are the government’s grant for key energy projects and the Ministry of Economic Affairs and Employment’s energy grant. These promote clean energy solutions in municipalities and companies, but residents in the form of households, housing companies and energy communities are excluded. For example, if a company wants to build a solar power plant on the roof of a municipality’s rest home with the power purchase agreement model, it cannot receive a grant because the solar electricity is used by the senior citizens. Citizens in countries like Sweden, Denmark, Lithuania, Japan, Uganda and Peru are within the scope of clean energy support schemes.

A carbon-free society cannot be built with centralised authoritative policy and by leaving citizens outside the energy transition. This kind of leadership model rarely inspires enthusiasm for change in democratic countries. The challenge with rapid social changes is the NIMBY (not in my backyard) phenomenon. It is understandable that people oppose change when new technologies enter their living environment. For example, wind power has been more accepted in Denmark and Germany than in Finland because the power plants were built by energy co-operatives made up of local farmers, entrepreneurs and residents.

Economic benefit sharing models and carrots, participatory planning, interactive communications, and opportunities to exert influence improve acceptance of new technologies and their implementation among citizens. This perspective hasn’t been utilised in Finland yet.

Finland has all the prerequisites to become a model country for the internet of energy solutions and a bilateral electricity market. We need a market reform that guarantees incentives for consumers to invest in clean energy solutions and easy access to the energy market. •