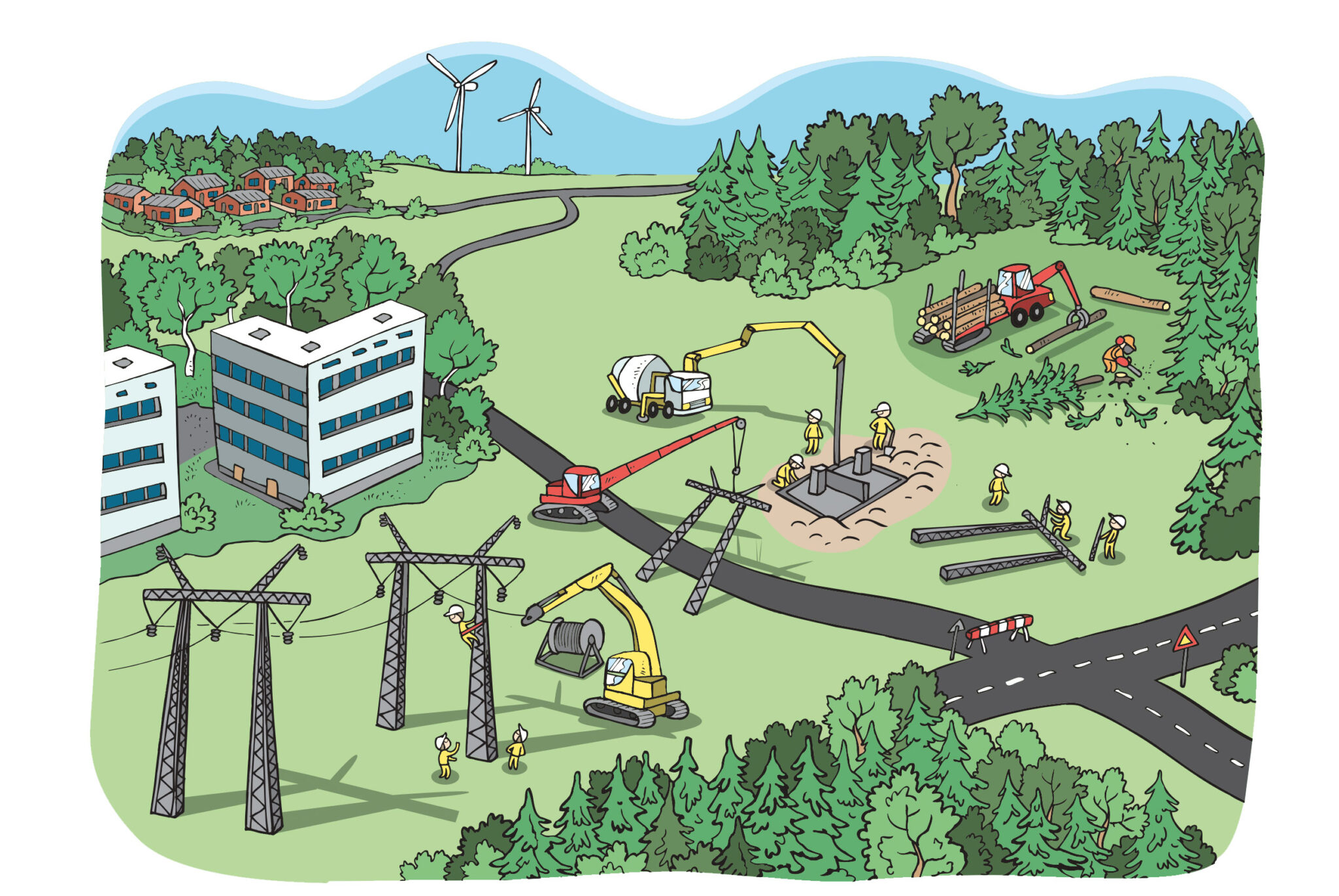

Archaeological excavations are part of Fingrid’s statutory environmental impact assessment (EIA, known as YVA in Finnish) for its transmission line project to assess the impacts of construction on people and the environment, and the possibilities to mitigate the impacts. Satu Vuorikoski, Fingrid’s Corporate Responsibility Development Manager, says that in a comprehensive background report, the Finnish Heritage Agency identified the need for an archaeological inventory survey, and on that basis the decision was made to carry out conclusive excavations.

“The excavation mean that we can confirm early on, in the planning phase, that the location of towers will not pose any threat to the preservation of archaeological values,” says Vuorikoski.

Researcher Vesa Laulumaa from the Finnish Heritage Agency’s archaeological field services monitors the excavator and now and again gives instructions to the excavator operator.

“There was a croft or two on this site, and archived information tells us that Stone Age tools were found here at the turn of the 20th century when the field was cleared for cultivation,” says Laulumaa.

Laulumaa can see the location of the crofts on a map of the parish from 1843. It is however more difficult to establish whether there was any settlement in this area during the Stone Age (approximately 8,600 – 1,500 BCE). Laulumaa believes that the place was just as nice back then. Steep hills surround the open area next to the riverbank, so the site would have provided warmth and protection. Hunter-gatherers also found their way to good fishing waters.

A charcoal pile under the topsoil

Laulumaa and Excavator Operators Ville Juntunen and Pekka Kolehmainen have first studied the highest ridges of the hilly field.  The field is now dry due to drainage.

The field is now dry due to drainage.

“In the spring at least, the lowest areas are so wet that no-one will have wanted to settle there,” the men hypothesise.

As the search progresses, the excavator makes its way to just a few metres from the edge of the field before Laulumaa gives the signal to the excavator cabin to stop the bucket. A glimpse of something black can be seen underneath the layer of sand and mud. Laulumaa carefully wipes away the soil and the find turns out to be a piece of charcoal.

The excavator carefully removes the soil, and the base of a charcoal pile with a diameter of 5.5 metres is revealed. A pile of wood around one metre tall has stood in this place, used for smouldering coals for smiths’ kilns, for example. Now there remains a round and even layer of charcoal with a reddish edge that indicates that the sand was burnt in a high heat. The find is familiar to Laulumaa.

“Charcoal piles are found here and there, but rarely on shores or coasts. Oulujoki used to be a significant transport route, and perhaps  the charcoal was taken from here for sale.

the charcoal was taken from here for sale.

Laulumaa says that from an archaeological perspective, a charcoal pile dating from the 16th – 18th centuries is not a very interesting find. Any Stone Age findings were however expected to have been lost when the fields were worked.

“These fields have been sown and tilled countless times,” confirms Seppo Kolehmainen, standing next to the excavator.

As it happens, we are standing on Kolehmainen’s land, where he spent his childhood. The farm passed down to him in a change of generation in the 1980s, but as demand for machine contracting grew, he took up contracting work in the 1990s.

“The charcoal pile was a surprising find. We had no idea it was there, and there’s never been any talk of finding Stone Age tools, either.”

Archaeological fieldwork progresses systematically, and the excavations are the next step after meticulous background work. Laulumaa explains that the location of rivers and shorelines in various ages are investigated using various material sources and different maps. One of the most useful sources of data is the laser scanning material from the National Land Survey of Finland. In practice, the material provides a three-dimensional map view that reveals even Stone Age settlements as depressions.

“In Finland, the topsoil grows so slowly that in fact, the majority of Stone Age items are found immediately underneath the top layer of soil.

Another charcoal find – a rare ancient field?

Next to the charcoal pile, a larger, irregularly shaped charred area was found, whose purpose remains a mystery. Laulumaa and researcher Esa Mikkola think it is possible that this was a rare, ancient field. This was investigated with carbon dating over the summer.

If the discovery was older than 13th century, the area would be studied more carefully and protected in order to avoid damage during construction of the transmission line. However, measurements taken at the end of July indicated that discoveries are from 14th to 16th centuries.

The location of 19th century crofts was also mapped in Tallikangas over the summer. Occupational health and safety plays a major role in excavations and surveys, since the 220-kilovolt transmission line built in 1949 between Muhos and Vaala runs across the field, and must be continuously taken into account during the surveys. There are precise safety distances from the transmission lines, which means that there are also precise safety areas around the sizeable towers.

Fingrid’s Specialist Risto Uusitalo explains that for safety reasons, no excavation will be carried out at a distance of less than three metres from the tower foundations or stay-cables, which are anchored with underground concrete slabs. Underground tower earthing will also remain outside of the excavation area.

“Luckily the lines in the tower near the excavation site are high up, and the minimum distance to the lines was a safe distance.”